When 2020 drew to a close, public health experts warned about a highly transmissible variant of SARS-CoV-2 — the virus that causes COVID-19 — first detected in the United

Kingdom (UK) in September and since documented in over 80 countries worldwide.

“It would be naïve of us to think that we will not get the new variants of SARS-CoV-2 in Nigeria,” Professor Christian Happi, a Harvard-trained geneticist and Director of the African Centre of Excellence for Genomics of Infectious Diseases (ACEGID) at Redeemer’s University in Ede, said. “Viruses, including SARS-CoV-2 mutate naturally overtime; so we expect it.”

The appearance of SARS-CoV-2 variants in Nigeria was only a question of when, not if. Last December, Happi’s team in Ede, Osun state, identified a new variant of SARS-CoV-2 in Nigeria. The report revealed that the new variant — later named B.1.525 — differed from the highly contagious UK coronavirus variant properly called B.1.1.7. But this February, they confirmed the B.1.1.7 variant in five states in Nigeria. “This lineage — first discovered in the UK — can infect people more readily, cause more severe illness and can lead to death,” the ACEGID lab warned via its Twitter account.

Our battle against COVID-19 seems never ending. The is uncertainty about the ongoing evolution of the pandemic as it continues to spread, it has become clear that like with all viruses, they mutate and adapt to survive. More transmissible coronavirus variants have emerged in countries including the UK, South Africa, and Brazil. Why the change? What do we know about the new variants? What do we do to best adapt?

Science Basics

All living organisms are made up of cells. All cells have genomes — genetic make-up — made of Deoxyribonucleic Acid (DNA), long strings of building blocks that carry information. Viruses, on the other hand, may have DNA or Ribonucleic Acid (RNA). Triplets of DNA or RNA bases convert the information into amino acids that link into proteins, and proteins underlie the functions or traits i.e. characteristics of a virus such as disease transmission.

The sequences of nucleic acids can change, when the molecules copy themselves, like continually making a typo in a document. These changes are known as mutations. Not all changes to DNA or RNA affect the encoded protein, but if they do, they can alter the corresponding trait. For a virus, that might be more efficient in transmitting to a new host, there is an increased risk of susceptible populations catching the virus, and leading to more cases of severe disease or death.

Why does the coronavirus mutate?

It is a natural phenomenon for viruses to change through mutation overtime. This happens when the virus makes an error, when its DNA or RNA is being replicated into host cells, or because of selective pressure caused by external agents — like the effects of chemicals or radiation — which affect the ability of an organism to survive in an environment.

A mutation in SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus, could confer an advantage to the virus. For instance, a virus with a helpful mutation could affect humans more readily, spreading more easily between people; it could be less recognised by our immune system, or more infectious. But the vast majority of mutations will have little impact.

“We can do nothing to prevent viruses from mutating. They do so naturally as a survival strategy,” Happi explained. “Mutation is one of the natural ways that the virus adapts to its environment. But it has no control over the way mutations occur.”

Thousands of SARS-CoV-2 variants are circulating worldwide, says Dr. Chikwe Ihekweazu, Director-General of the Nigeria Centre for Disease Control (NCDC). Ihekweazu explained that new variants are in themselves not a cause for alarm unless they have acquired “a series of mutations that makes them to be more deadly.” These mutant variants are known as “variants of concern.”

“We have in found in Nigeria some of the UK variant of concern,” Ihekweazu said. “The Nigerian variant B.1525 is in itself not a challenge. We know that there is a new variant but we need to do more investigation to find out if there is any associated difference not just in transmissibility but in severity, loss of vaccine efficacy or ability to evade existing tests that detect the virus.”

What do we know about coronavirus variants in Nigeria?

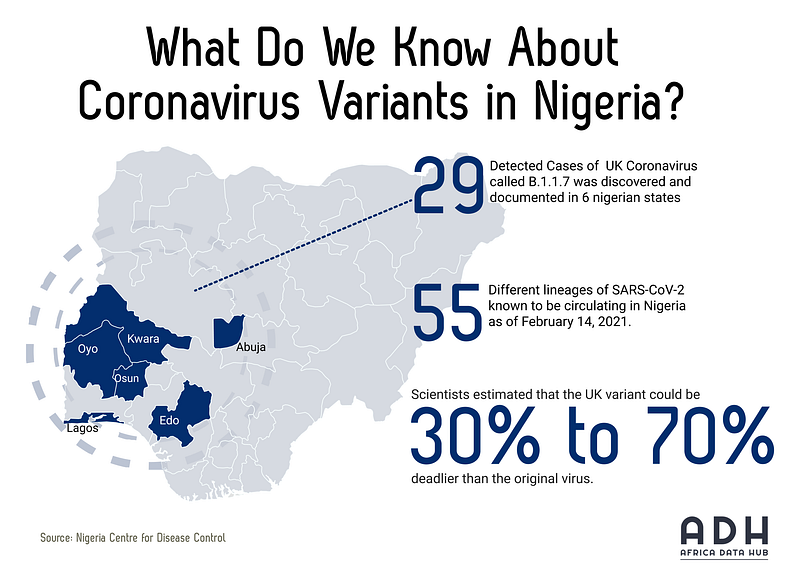

As at February 14, 2021, there are about 55 different lineages of SARS-CoV-2 known to be circulating in Nigeria and they are changing rapidly. The diversity of SARS-CoV-2 strains indicate multiple introductions of the virus into Nigeria from different parts of the world and adds to evidence of community transmission in different states of Nigeria, according to a recent statement by NCDC.

There are 29 detected cases of the UK coronavirus variant B.1.1.7 in Nigeria. The variant was identified in samples collected from patients between November 2020 and January 2021, according to NCDC, and documented in 5 states: Edo, Kwara, Lagos, Oyo, Osun, and Abuja.

On the other hand, the first detected B.1.525 case in Nigeria was in a sample collected on the 23rd of November from a patient in Lagos State. So far, this has been detected among cases in five states in Nigeria. B.1.525 cases have also been reported in other countries in travelers from Nigeria, according to NCDC. “Currently there is no evidence to indicate that in Nigeria,” said the statement. “Therefore B.1.525 is a new strain, but not yet a variant of concern and further analysis is ongoing.”

The UK variant harbors several mutations that enable viruses to copy themselves faster, spread from host-to-host more readily, and bind more tenaciously to our cells. Happi said it has probably been more widespread in Nigeria, but have yet to be detected because “we aren’t looking through genomic surveillance.”

Is the UK variant more transmissible and deadlier?

According to British government scientists, the coronavirus variant first detected in the UK — known as B.1.1.7 — is more transmissible and likely more deadly than the original strain. In their report, which evaluated multiple studies, the scientists estimated that the UK variant could be 30% to 70% deadlier than the original virus.

Asked if this could be true for Nigerians, Happi said: “Although scientists are working to learn more about the characteristics of the UK variant, the information we have now is clear — it is associated with increased disease and death. The virus can invade cells much faster and more efficiently, and when it does that, it means you will have an overwhelming number of viruses that invade your cells and therefore the damage is much more.”

Happi explained that the variant first detected in the UK has several mutations in the spike protein gene — the part that the immune response “sees” — so when the virus mutate the host’s antibodies could become ineffective against the virus, leading to severe disease and death.

How best do we respond?

As viruses mutate over time, there is always a danger of them becoming resistant to our natural immune defenses, including vaccines and antibody therapies. This represents a threat to all the vaccines developed and ending the coronavirus pandemic. For example, South Africa has recently suspended its rollout of the Oxford/AstraZeneca vaccine after a preliminary study found it provided limited protection against the South African coronavirus variant, for mild and moderate cases of COVID-19. The variant has been found worldwide, including in the US. It has presented challenges for all the available COVID-19 vaccines, compromising their effectiveness to different extents.

Happi warned that “the risk is big for Nigeria; hence, the government should continue to enforce the non-pharmaceutical method of prevention: wearing facemask, hand washing and social distancing in every part of the country. If we keep spreading this virus, there will come a time when we will not have a chance to protect ourselves — we have no better option now than prevention.”

Real-time genomic surveillance across all regions of Nigeria is critical to track new variants and clinical research is necessary to understand why they may be of concern. A recently issued statement from the NCDC mentioned that a process was being put in place to carry out systematic genomic surveillance for SARS-CoV-2 in Nigeria. There may also be a need to confirm whether current precautions, decontamination procedures and therapies are still valid and if required, adapt public health responses based on guidelines by the Nigeria Centre for Disease Control (NCDC). However, there is currently no evidence that this may be necessary in view of the variants of concern circulating.

High transmission rates of COVID-19 will stoke the fire by disseminating new variants more rapidly and increasing the odds of more mutations in the future. So, we must all take responsibility to stop the virus from spreading in Nigeria. This means practicing physical distancing, washing hands regularly and wearing masks when meeting people, even when they are hesitant to do the same.

“The risk is for everybody,” Happy says. “But you can’t spread the virus if you take steps to avoid doing so.”

The conversations around mutations will continue as long as the COVID-19 virus is still circulating. However, the good news is the arrival of 3.9 million doses of COVID-19 vaccines in Nigeria, on the 2nd of March 2021. These were supplied through the COVAX facility and is a step in the right direction. COVID-19 vaccines remain the best bet in limiting the spread of the virus and the potential for further variants of concern to emerge. Even though further mutations will occur in the future, globally we must push for the majority of our population, starting with those most at risk, such as health workers and vulnerable populations to be vaccinated, only then can we return our lives back to some semblance of normality.